I have done some reading from time to time on the relationship between nature and grace in Christian theology. It seems to function in the background of a number of important topics, including the relationship between faith and reason, religion and science, and Christianity and culture, and so I find myself returning to it every once in a while. My own introduction to these concepts came in seminary, where I took a class on theology and culture. Particularly helpful was reading H. Richard Niebuhr’s book, Christ and Culture (1951), in which he surveys Christian attempts to grapple with the question of how to relate the Christian faith to the resources of human culture.

![1,300,000+ Best Free Nature Pictures & Images [HD] - Pixabay](https://cdn.pixabay.com/photo/2014/02/27/16/10/flowers-276014_640.jpg) To explain the topic succinctly, the question of nature and grace has to do with how created things, and specifically human beings, relate to the grace of God in Christ. It has to do with the relationships between the most comprehensive categories of Christian theology, such as creation, sin, and redemption; the relationship between creation and new creation; and as I mentioned above, a number of controversial topics take place downstream.

To explain the topic succinctly, the question of nature and grace has to do with how created things, and specifically human beings, relate to the grace of God in Christ. It has to do with the relationships between the most comprehensive categories of Christian theology, such as creation, sin, and redemption; the relationship between creation and new creation; and as I mentioned above, a number of controversial topics take place downstream.

Here are some examples of the kind of questions that are raised in downstream from this question:

- When it comes to knowing God, should we pay attention to human reflections on creation (nature), or the supernatural revelation given in the Bible (grace)?

- When it comes to determining who “gets into heaven,” is it determined by what we do (nature), or by what God has done (grace)?

- When it comes to interacting with the broader culture (e.g., philosophy, entertainment, etc.), should we view it as good (nature) or bad (grace)?

- When we’re reading the Bible, should we listen to Bible scholars (nature), or the Holy Spirit (grace)?

- When we want to understand human origins, should we turn to scientists (nature), or theologians (grace)?

- When it comes to spirituality, do we work with our bodies and minds (nature), or apart from them (grace)?

- When I experience mental health challenges, do I need a a therapist (nature), or a pastor (grace)?

- When it comes to raising children, should we teach them morals (nature), or the gospel (grace)?

- When I get sick, do I need to see a doctor (nature), or pray (grace)?

Many of these contrasts are obviously exaggerated to make a point. However, in general, non-Christians and more liberal Christians tend to track mostly on the “nature” side of these disjunctive statements, and Christians who are more on the fundamentalist side (along with some more conservative evangelicals) would trend generally toward the “grace” side. Various other Christian groups (some evangelicals, Catholics, etc.) would look for some way to bring them together in some sense.

A big part of my interest in this topic comes from working through various theological and pastoral issues and noticing similar underlying principles at play. I was raised as a more-or-less secular liberal, and after conversion I was immersed in the fundamentalist culture in Bible college. Since then, I have moved toward a more evangelical stance, but much of the way my life has developed over the past couple decades has had to do with shifts in how I relate nature to grace.

What I’ll do in the rest of this post is give a brief overview of the history of this discussion, and then give my own reflections on the topic, and finally a short bibliography of helpful resources on this topic.

History of the Reflection on Nature and Grace

Reflection on the relationship between nature and grace reaches back to the earliest times. Henry Stob notes that early Christians had to come to terms with how to relate what God has done for us in Christ to human reflection on the world in the form of Hellenism and Greek philosophy. Some, such as the church father Tertullian rejected any concord between these two principles. He famously said “What indeed has Athens to do with Jerusalem? What concord is there between the Academy and the Church? what between heretics and Christians?” (Against Heretics, 7). Others more-or-less equated the two (including the father Justin Martyr and early Gnostics). However, the majority position throughout the history of the church has been some kind of concord between the two that does not collapse them into one another, nor place them in opposition to each other.

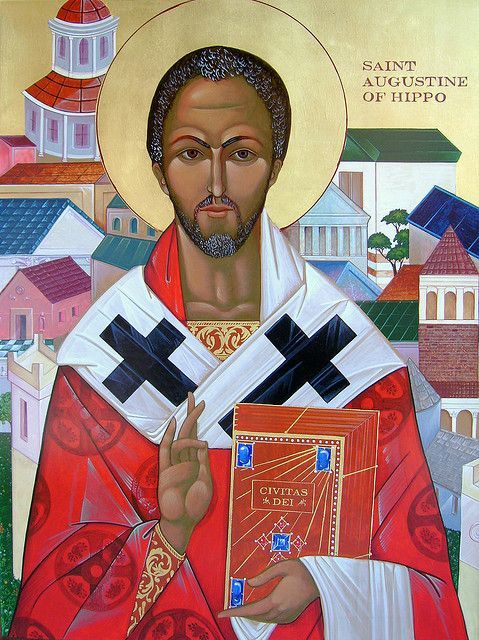

With reference to the question of human learning, Augustine gave us the famous metaphor of “plundering Egyptian gold.” As he says in De Doctrina Christiana 40:

Moreover, if those who are called philosophers, and especially the Platonists, have said aught that is true and in harmony with our faith, we are not only not to shrink from it, but to claim it for our own use from those who have unlawful possession of it.

For, as the Egyptians had not only the idols and heavy burdens which the people of Israel hated and fled from, but also vessels and ornaments of gold and silver, and garments, which the same people when going out of Egypt appropriated to themselves, designing them for a better use, not doing this on their own authority, but by the command of God, the Egyptians themselves, in their ignorance, providing them with things which they themselves were not making a good use of; in the same way all branches of heathen learning have not only false and superstitious fancies and heavy burdens of unnecessary toil, which every one of us, when going out under the leadership of Christ from the fellowship of the heathen, ought to abhor and avoid; but they contain also liberal instruction which is better adapted to the use of the truth, and some most excellent precepts of morality; and some truths in regard even to the worship of the One God are found among them.

Now these are, so to speak, their gold and silver, which they did not create themselves, but dug out of the mines of God’s providence which are everywhere scattered abroad, and are perversely and unlawfully prostituting to the worship of devils. These, therefore, the Christian, when he separates himself in spirit from the miserable fellowship of these men, ought to take away from them, and to devote to their proper use in preaching the gospel.

With regard to the work of God in salvation, Augustine’s book, On Nature and Grace, gives a very early articulation of the problem of nature and grace in response to Pelagius, who affirmed that human nature was perfectable apart from divine grace. In contrast, Augustine cites, for example, Paul’s words in Gal 2:21 (“If righteousness could be gained through the law [or any work of human nature], then Christ died for no reason”) and Jesus’ words in Luke 5:31–32 (“It is not the healthy, but the sick who need a doctor. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners, to repentance”) to show that fallen humanity requires divine grace for salvation because sin has wounded our nature (ch. 12). In short, Augustine defends the necessity of attending to both grace and nature.

Thomas Aquinas provided the Roman Catholic Church with a definitive paradigm for relating nature to grace through a synthesis of Christianity with Aristotelian philosophy. According to the New Catholic Encyclopedia,

He clearly affirmed that while grace now is necessary to heal wounded nature, its primary function, which it would have in any hypothesis, is to elevate nature to a share in the properly divine nature (Summa theologiae 1a, 95.4 ad 1). Grace is supernature, rooted in nature and making nature transcend itself. St. Thomas affirmed the existence in every intellectual nature of a capacity for this elevation—a teaching that would subsequently find many different interpretations.

He clearly affirmed that while grace now is necessary to heal wounded nature, its primary function, which it would have in any hypothesis, is to elevate nature to a share in the properly divine nature (Summa theologiae 1a, 95.4 ad 1). Grace is supernature, rooted in nature and making nature transcend itself. St. Thomas affirmed the existence in every intellectual nature of a capacity for this elevation—a teaching that would subsequently find many different interpretations.

Aquinas’s system is like a house with two-stories–a bottom story (nature) that is damaged, but essentially has its own integrity, and a top story (grace), which is added to nature and provides what is not attainable by nature. This can be seen in Aquinas’s proofs for God’s existence: he believes that creation (nature) shows that there is a God, but you need revelation (grace) to know that he is a Trinity.

As Eugene TeSelle noted, the Reformers did not have a theory of nature and grace per se (“Ecumenical Discussion”). However, as part of the broader response to Roman Catholicism, the Protestant Reformers implicitly critiqued the way Roman Catholicism downplayed the effect of sin on the ability of unbelievers to understand truth. The Dutch Reformed, especially Herman Bavinck, have articulated the relationship under the heading of the phrase “grace restores nature.” As it is articulated in Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture, this approach goes under the label “conversionist.” When I was in seminary there was a revival of interest in talking about engaging with culture along these lines, and the way this was often described was by saying that creation is “structurally good” but “misdirected.” As Bruce Ashford says,

As Eugene TeSelle noted, the Reformers did not have a theory of nature and grace per se (“Ecumenical Discussion”). However, as part of the broader response to Roman Catholicism, the Protestant Reformers implicitly critiqued the way Roman Catholicism downplayed the effect of sin on the ability of unbelievers to understand truth. The Dutch Reformed, especially Herman Bavinck, have articulated the relationship under the heading of the phrase “grace restores nature.” As it is articulated in Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture, this approach goes under the label “conversionist.” When I was in seminary there was a revival of interest in talking about engaging with culture along these lines, and the way this was often described was by saying that creation is “structurally good” but “misdirected.” As Bruce Ashford says,

In this view, sin does not have the power to corrupt the natural realm structurally. Instead, it corrupts the natural realm directionally. God’s still-good-structurally creation is misdirected toward false gods and idols. When Christians receive God’s grace in salvation, they are liberated from their idolatry, liberated to shape their cultural activities toward Christ rather than toward false gods and idols. Their cultural activity is redirective.

In this way, Christians who work from the Dutch Reformed perspective tend to think of grace as remedial to nature.

One recent movement amongst Roman Catholics that has readdressed this questions is the nouvelle théologie movement in the mid 1900s, including such figures as Henri De Lubac and Karl Rahner. This movement, also called ressourcement, has impacted both Catholics (esp. in Vatican II) and protestants through a renewed interest in theological retrieval. As I understand it, a central question throughout these debates was the question of whether grace is intrinsic or extrinsic to nature. According to Leonardo De Chirico,

One recent movement amongst Roman Catholics that has readdressed this questions is the nouvelle théologie movement in the mid 1900s, including such figures as Henri De Lubac and Karl Rahner. This movement, also called ressourcement, has impacted both Catholics (esp. in Vatican II) and protestants through a renewed interest in theological retrieval. As I understand it, a central question throughout these debates was the question of whether grace is intrinsic or extrinsic to nature. According to Leonardo De Chirico,

The perception of these new theologians was that, after the Council of Trent, Thomas Aquinas’ account of nature and grace had been hardened to the point of making nature and grace “extrinsic,” i.e. separate, sealed off, apart from one another, resulting in a static outlook of a super-imposition of grace on top of nature. In his seminal work Surnaturel (1946) and in subsequent books, De Lubac in particular argued that this rigid interpretation of Thomas Aquinas had brought about a dichotomy between nature and grace, losing therefore the continuity between the two. Nature and grace had become juxtaposed rather than integrated, with grace being associated with a superior degree of nature rather than its original and pervasive matrix. Grace needed to be re-thought of as immanent to nature, as nature was to be re-appreciated as organically open and disposed to grace. According to this view, grace is not added to nature as though nature is void of it; rather grace is always part of nature as a constitutive element of it.

This starts getting a little intramural for me and more nuanced than I have time to explore at the present. De Chirico credits the adoption of this viewpoint with a further minimization of sin and some of the more (theologically) liberal moves that the Catholic church has made in the past century, but I am not familiar enough with the issues to adjudicate that assessment.

The upshot of the above survey is that the relationship between nature and grace is a central question within Christian theology and is dealt with implicitly in most theological systems. However, it generally has only received explicit teaching in the Roman Catholic Church, where the interdependence of nature and grace is normative.

Concluding reflections:

- The nature-grace dichotomy is a helpful heuristic for correlating a number of distinct, but related areas of theological inquiry. It provides some big-picture categories.

- There are some weaknesses as well. It can, at times, lead to oversimplification. In each of the dichotomies I cited in the beginning of this post, there are particulars that need to be taken into account. There are also particular theological issues that need to be ironed out, such as the relationships between nature and supernature, creation and new creation, and the work of the Spirit in sanctification. The nature-grace dichotomy can function like a map of the world–it can give you a sense of the big picture, but is not very helpful for finding something in the town you live in because it’s not functioning at that level of detail.

- Protestant critiques of Roman Catholicism rightly point out that the nature-grace dichotomy, especially as it’s articulated in the Catholic tradition, often neglects or downplays sin.

- I’m inclined to think there is also something to the Roman Catholic critiques that Protestants sometimes too sharply oppose nature and grace (though Protestants are far from monolithic). Whereas Catholics tend to focus on grace and nature, Protestants tend to focus on grace and sin. The issue is how to triangulate the relationship between grace, nature, and sin.

- My gut feeling is that the Enlightenment presented a watershed with regard to how we thought about “nature” and resulted in a theological shakeup in how Christians related nature and grace. Perhaps Vatican II and the nouvelle théologie movement were a reaction to this? The fundamentalist-modernist controversy most certainly was.

- Two significant errors in this area are theological liberalism, in which nature swallows up grace (divinizing nature), and fundamentalism, which opposes grace to nature (obliterating nature). The rest of us are generally working on trying to hold on to both, and to somehow rightly relate them.

- My own amateur reflections (and I stress the word amateur) are as follows:

- Grace assumes nature. Nature is the “stuff” with which grace works. For this reason, we have to work “with the grain” of nature (though not with the grain of sin). For this reason, a better understanding of nature generally leads to better discipleship.

- Grace heals nature. Augustine is right to point out that Scripture presents the salvation that we have in Christ as a cure for the problem of the fall and sin. With Athanasius, we need to affirm that what God does for us in Christ is restorative. Grace actually restores our true humanity. For this reason, people need more than psychological techniques and self-help advice; they need a supernatural savior.

- Grace extends nature. Here I part with some in the Reformed tradition that affirm the previous point in such a way that makes it sound like what God does for us is simply to restore us to what Adam would have been like had he not sinned. However, I understand that the new creation will have both significant continuities with the present creation and significant discontinuities. One clear passage with this regard is 1 Cor 15:35–57, where Paul says that our present bodies are related to our resurrection bodies like a seed is related to a tree: as a tree is organically identical to the seed that is planted in the ground and yet ends up radically different in result, so our resurrection bodies have both identity and radical difference in relation to our present physical bodies. From this and other passages, I tentatively conclude that while grace is in some sense restorative of our nature, in another sense its fulfillment will be beyond our present nature.

Bibliography

Augustine, On Nature and Grace (De natura et gratia).

Stob, Henry. “Nature, Sin, Grace: Calvin and Aquinas” The Reformed Journal (1974). This is an excellent introduction into the origins of the discussion about nature and grace and addresses the heart of the difference between the Thomist and Calvinist solution to the problem. It also shows how the problem is not merely one of nature vs. grace, but the relationship between nature, grace, and sin.

Niebuhr, H. Richard. Christ and Culture (1951). This is a classic starting point for this discussion because, for better or worse, he has set the tone for the discussion of these topics by means of his typology. While various criticisms can be made about the way he sets up his categories, this is a thoughtful engagement with the issues (summarized here by Trevin Wax).

New Catholic Encyclopedia. “Grace and Nature.” A good overview of the issues, focusing on the Catholic tradition.

Ashford, Bruce. “What Does Grace Have to Do with Nature? (Or What Is the Relationship between Christ and Culture, or the Bible and Higher Education?).” The Gospel Coalition.

De Chirico, Leonardo. “A Historical Sketch of the Nature-Grace Interdependence.” The Vatican Files. This three part blog series gives a great detailed summary on the Catholic teaching about nature and grace. From a Protestant perspective.